In this article

Review some of the most commonly asked questions about brain arteriovenous malformation:

What is an arteriovenous malformation?

Typically arteries carry blood with oxygen from the heart to the brain and veins carry blood with less oxygen away from the brain and back to the heart. An arteriovenous malformation, also known as AVM, involves a tangled nest of blood vessels that bypasses normal brain tissue and directly diverts high pressure blood from the arteries to the veins.

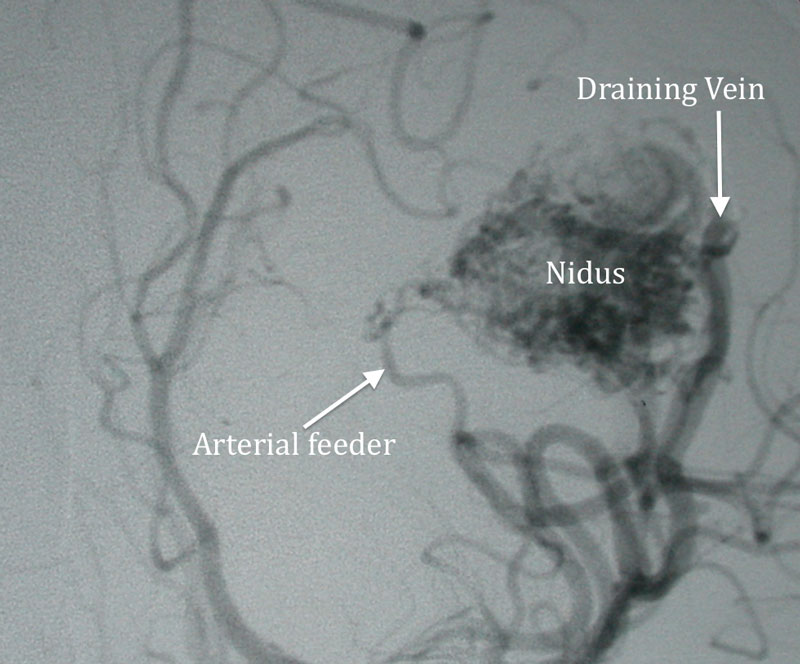

An arteriovenous malformation is a developmental vascular abnormality characterized by a tangle of vessels shunting blood directly from arterial to the venous system (Figure 1). Capillaries, the microscopic vascular channels that are typically interposed between an artery and vein, are not present in an AVM. Capillaries are necessary in human physiology because they allow for the delivery and exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide to and from tissue. A natural consequence of blood flow through a capillary system, furthermore, is a reduction of blood pressure from an arterial mean of 80-90mm Hg to venous pressure which hovers at 3-8mm Hg. The alteration in normal cerebral blood flow found in AVM-pressurized blood flow in thin walled venous channels has clinically significant implications including hemorrhage, brain swelling and seizures.

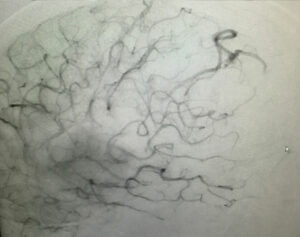

Figure 1

Arterial phase cerebral angiogram demonstrating a large left parietal AVM. Nidus or the center of the AVM is indicated along with feeding arteries and draining vein.

How common are brain AVMs?

Brain AVMs are more common in males than in females and occur in less than 1% of the population.

Why do brain AVMs occur?

Brain AVMs are thought to be congenital, meaning it is a condition someone is born with or that it develops during childhood. However, brain AVMs are not usually hereditary. Brain AVMs can occur anywhere within the brain or spine.

What are the symptoms or clinical presentations of a brain AVM?

Specific symptoms will vary depending on the location of the AVM. Potential symptoms may include:

- Many patients will have minimal or no symptoms.

- Some patients will report intermittent headaches.

- Some patients may experience stroke-like symptoms including focal numbness, weakness, visual changes or difficulty speaking.

- 20% to 25% of AVM patients have a seizure or epilepsy from the AVM.

- If the AVM ruptures and bleeds there can be severe, sudden onset symptoms such as severe headache, seizures, paralysis, confusion, vomiting or lethargy. A ruptured brain AVM is an emergency situation.

Arteriovenous malformations are often identified incidentally before the patient has developed any symptoms. In this circumstance, the decision to offer treatment depends on a careful consideration of the risks imposed by the natural history of AVM counterbalanced with the risks of treatment. The overall the annualized risk of internal bleeding from a ruptured AVM range from 2-3% and influenced by the details of its vascular anatomy, its location in the brain, size and history of previous rupture. These factors together with patient age and general medical status contribute to the calculus of management.

What causes brain AVMs to bleed?

A brain AVM is a nest of abnormal, weakened blood vessels that direct high pressure blood away from normal brain tissue. These blood vessels over time may rupture from the high pressure of blood within the malformation. A ruptured AVM is a life threatening emergency and will cause bleeding within the brain. The extent of brain injury is proportional to how much bleeding has occurred and which part of the brain is affected.

The risk of a brain AVM bleeding is approximately 1% to 3% each year. The risk of death from a brain AVM bleeding is 10% to 15% per episode of bleeding. Meanwhile, the chance of permanent brain damage is 20% to 30% per episode of bleeding. When blood leaks into the brain, normal brain tissues are damaged. This brain tissue damage results in a loss of normal function, which may be permanent or temporary.

Are there different types of brain AVMs?

Below are the following types of brain AVMs:

- True arteriovenous malformation: This is the most common type of brain vascular malformation. It consists of a tangling of abnormal vessels that connect arteries and veins with no normal intervening brain tissue.

- Cavernous malformations/ cavernoma : This is a low flow vascular malformation in the brain that does not actively divert large amounts of blood. This condition may cause bleeding and produce seizures.

- Venous malformation: This condition only involves an abnormality of the veins that is typically congenital and has a very low risk of bleeding.

- Dural arteriovenous fistula: This consists of an abnormal connection between blood vessels that involve only the surface covering of the brain.

How are AVMs diagnosed?

Most AVMs are diagnosed with either a CT scan or an MRI scan. An angiogram may be needed in order to better identify the type of AVM, its size and a detailed analysis of the AVM structure..

AVM rupture is a serious event and is heralded by headache, nausea, vomiting, paralysis, loss of consciousness and other neurological symptoms. Diagnosis of intra-cerebral hemorrhage is established and well characterized with head CT and often the pattern of bleeding suggests the presence of an AVM. Further studies including CT angiography, MR and MR angiography support the diagnosis and provide localizing anatomical information. A definitive understanding of the anatomy of AVM is obtained from cerebral angiography. An AVM is a complex 3 dimensional structure and often involves multiple feeding arteries together with unpredictably positioned draining veins. Angiography provides anatomical clarity as well as an understanding of the nature of the pathophysiology of its blood flow.

What is the best treatment for an AVM?

There are different medical treatments for an AVM. The following treatment options include:

- Medical therapy: Conservative treatment, such as controlling blood pressure, seizures and observing for any new symptoms over time.

- Surgical removal of the AVM: Surgery may be recommended if an AVM has bled or if it is in an area that can be easily accessed.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery: If an AVM is not too large, but is in an area that is difficult to reach via regular surgery, it may be treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. This treatment does not involve any incisions. The procedure involves performing a cerebral angiogram to localize the AVM. Then, focused-beam high energy sources are concentrated on the AVM. The AVM may be gone in 2-3 years after radiosurgery.

- AVM embolization: A minimally invasive procedure in which small catheters are used to fill portions of the AVM with “glue”, or liquid embolic agent. The AVM is shrunken gradually by embolizing and blocking the feeding arteries. Embolization can be done as part of a multistage treatment plan that later involves surgery or radiation treatment.

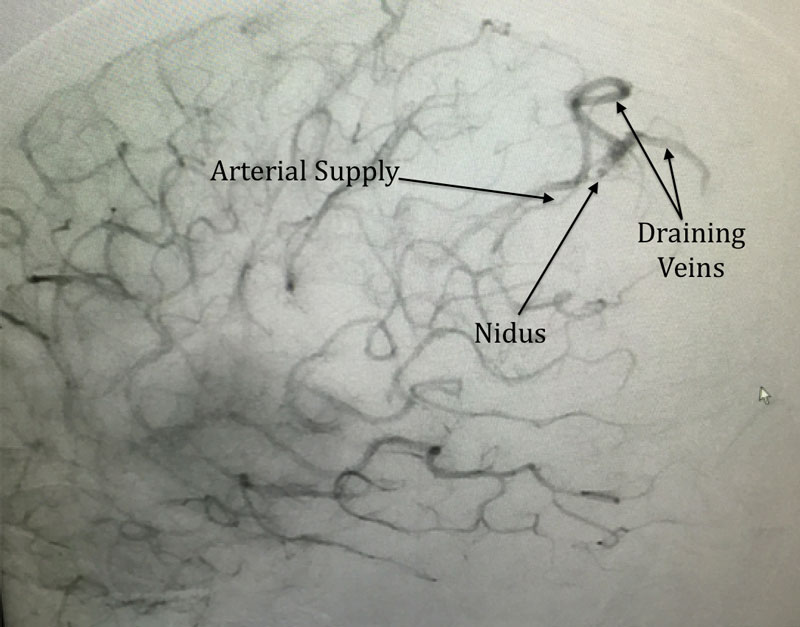

Treatment of the patient depends first on assuring that there is no ongoing internal bleeding and second by ameliorating the deleterious effect of bleeding and brain swelling. Craniotomy or craniectomy to remove the coagulum is sometimes performed in more critically ill patients to prevent injury to as yet uninjured brain tissue. In more mild cases, hemorrhage and brain swelling may improve with supportive care only. After the patient is stabilized, further interventions are offered to prevent rebleeding and obliterate the AVM. Treatment options include craniotomy for resection, endovascular embolization (Figure 2,3), radiosurgery (Figure 4 Gamma Knife), or combined/staged treatments. The anatomy, size, and location of the AVM are but some of the factors considered by the neurovascular team in formulating the plan of care.

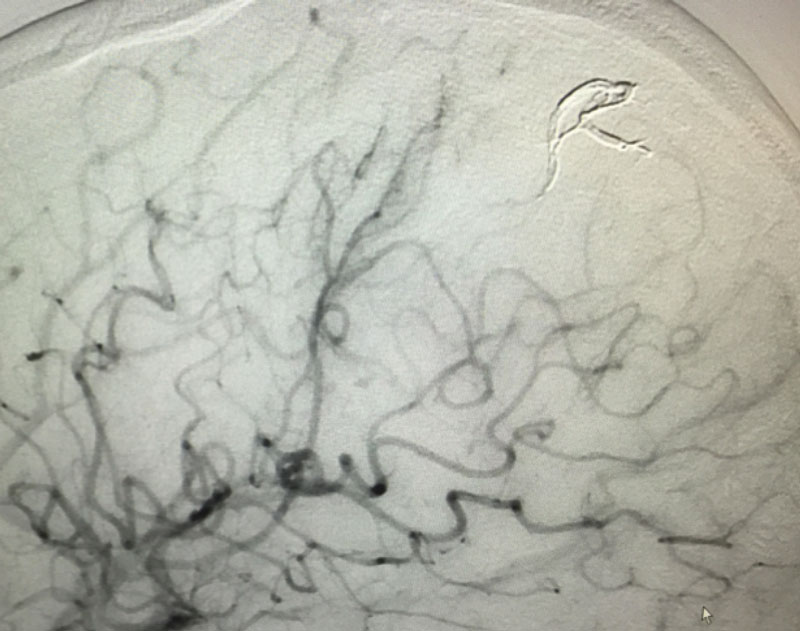

Figure 2

Lateral late arterial phase cerebral angiogram showing a small posterior parietal AVM with indicated arterial supply, nidus and draining vein.

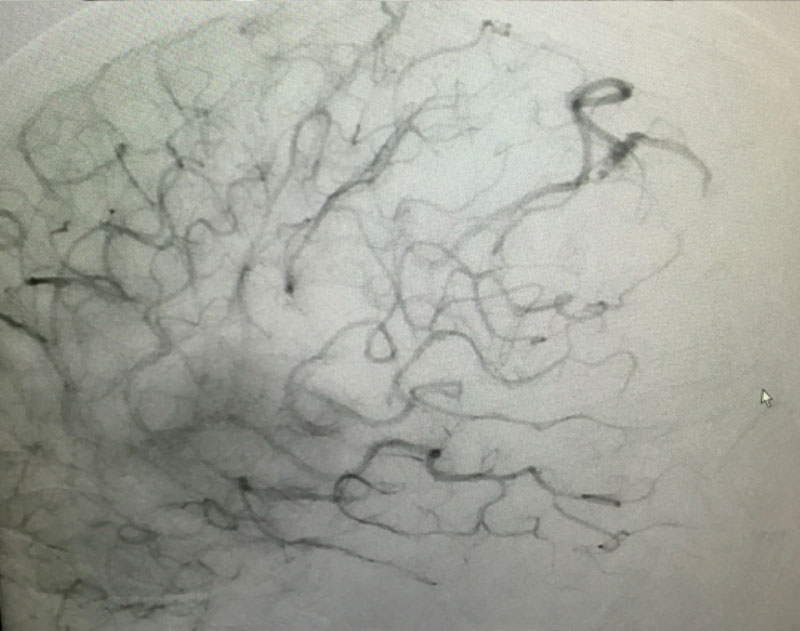

Figure 3

Same patient as above with before and after images superimposed showing embolic material filling the nidus and draining vein.

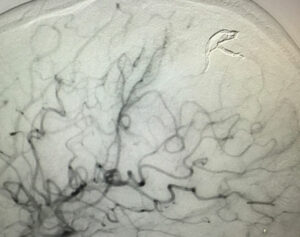

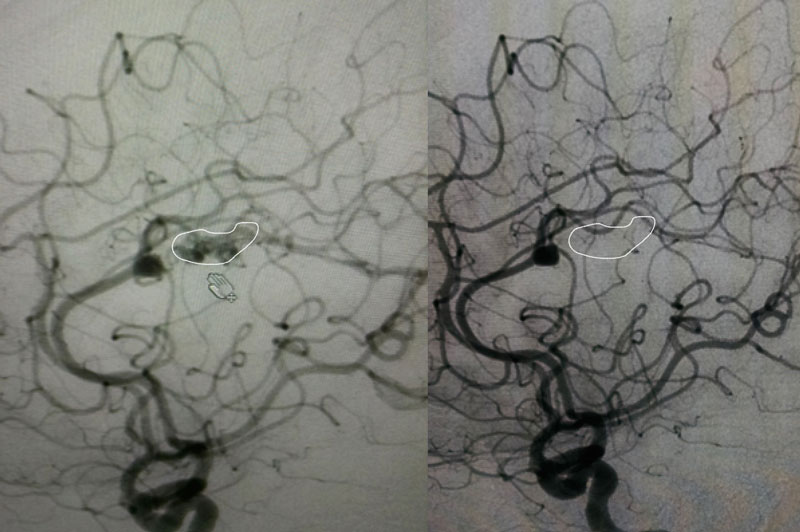

Figure 4

Lateral cerebral angiogram showing small AVM encircled by white line. Right: One year post gamma knife angiogram showing absence of filling (white line indicates estimated location of target) proving obliteration of AVM.